“As long as people are alive, the heritage cannot be destroyed”: an interview with Iryna Sklokina, a researcher at the Centre for Urban History

09/02/2023

Iryna Sklokina is a candidate for historical sciences and has been working as a researcher at the Centre for Urban History for seven years.

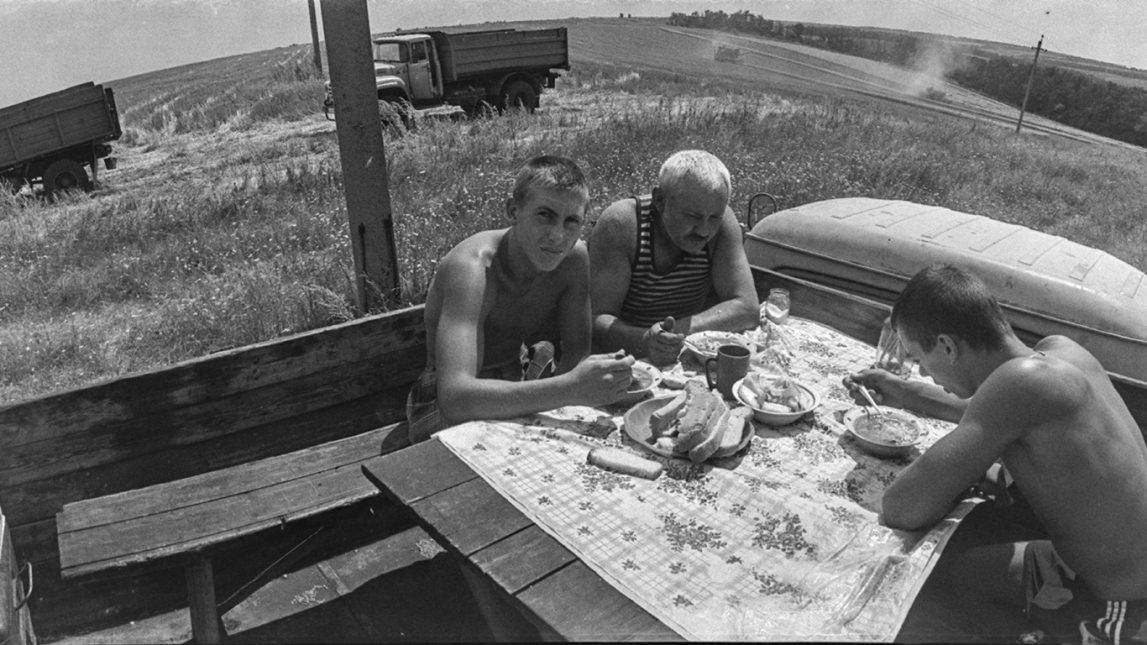

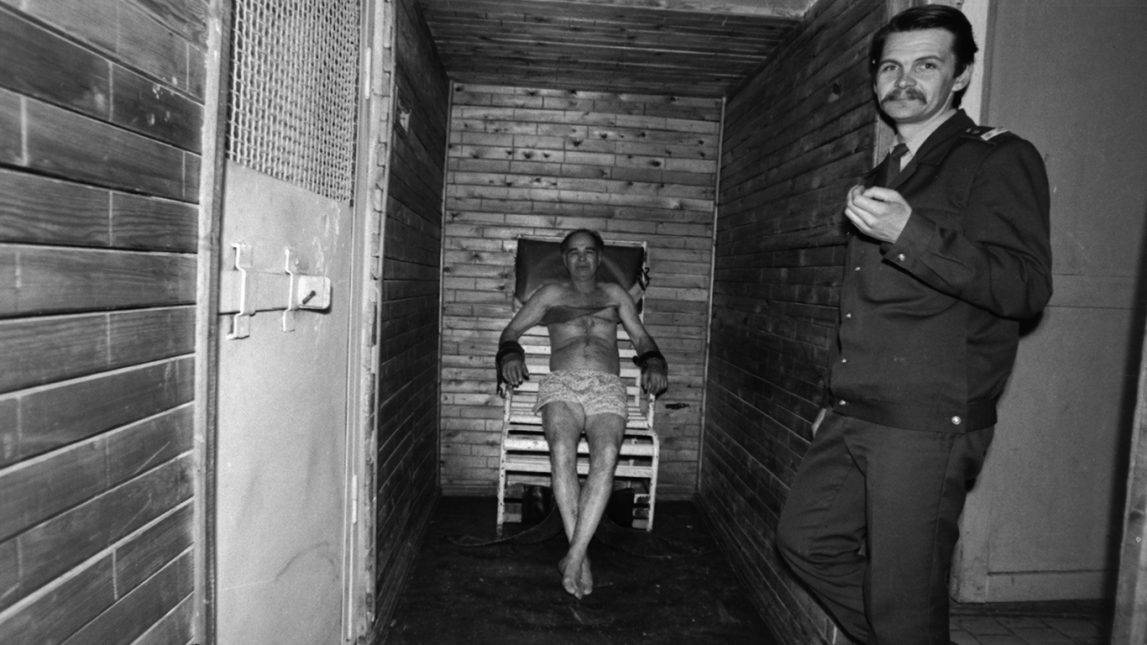

In 2020-2021, the Centre for Urban History in partnership with the University of St. Andrews and museums in Pokrovsk and Mariupol received an International Cooperation Grant from the House of Europe for the project Un/archiving Post/Industry that collected materials from the Mariupol Local Lore Museum, the Pokrovsk Historical Museum and several private collections into a digital archive showing everyday life in industrial cities.

We asked Iryna about the mysterious course of urban history, preserving the memory of cities destroyed by Russian invaders, the importance of archives, and the gentle decommunisation. In the article, you can read what came out of that.

Our conversation takes place during the full-scale war that Russia launched against Ukraine, where one of the enemy’s tasks is to destroy Ukrainian history, heritage, and culture, that is everything that you diligently archive and research at the Centre. Therefore, I would like to dedicate this interview to your activities in wartime and to understanding the current processes.

But let’s start with the basics: in simple terms, what is urban history?

The Centre for Urban History explores the history of the 19th-21st centuries. This is the time when modern society was formed due to the formation of mass society and industrialisation.

Urbanisation played a key role in this process. It was in the cities that modern identities were formed: the working class, elites, and great ideologies. There appeared political movements, civil society, and public organisations. That is what we study.

Of course, cities existed long before the XIX century, but back then the difference between them and rural districts was quite conditional.

There is an opinion that history is something far from everyday life. How the opening of a centre for urban history can help Ukrainian cities?

Sometimes, directly. We have a huge collection of works by Atanas Nykyforuk, a photographer who recorded facades of buildings in the 1970s and 1980s. Today, it is a database for restoration: for restoration of historical gates, balconies, doors, and windows.

The research related to Jewish history helps to change the urban space of Lviv. For example, the Golden Rose project is a memorial space created on the basis of an old synagogue. Thanks to historical research, community involvement, international support, and city council funding, Lviv received a new public space that honours its Jewish history.

With the support of the House of Europe, we digitised the collections related to the industry. In particular, the card index of portraits of the Lviv Bus-Making Factory workers. We hope to identify these people, talk to their relatives, and thus restore their family history. This is a very practical task: to give people a sense of belonging and the right to their city. Especially in the city of Lviv which does not want to reflect on its Soviet past. This is what unites a huge number of people in the city.

Let us go back to the war. We see that Russian forces are purposefully destroying our architectural monuments, churches, and museums. Is it possible to destroy the memory of the city together with its monuments?

It depends on the community’s desire to preserve its history. As long as people are alive, the heritage cannot be destroyed. If the community has a passion for its heritage and wants to unite around it and because of it, then even the heritage of Mariupol will endure.

The past also remains in the digital. For example, thanks to the House of Europe, we managed to digitise several thousand photos from the Mariupol Local Lore Museum. Today, the museum no longer exists: not only because of military activities but also because of looting.

What can we do to preserve our heritage?

It is important not just to preserve objects, but also to give them a new life.

For example, the idea of the Un/archiving Post/Industry project was to create a circle of artifact circulations. First, it was contact with the owners of archives, personal and institutional ones. Then, there were communication, digitisation, and recording of stories and explanations for photos and films.

The next step was a summer school that brought together artists, researchers, historians, and museum workers from Great Britain, the USA, and Ukraine. All of them proposed new use of the digitised materials: collages, installations, digital works, video art, and texts, based on which we created the exhibition.

After all, there was a dialogue. We put the digitised photos on the website and people started sharing them. The photos are reposted and discussed on social networks. This is how the heritage exists. It is used, updated, and debated.

Along with buildings, archives burn. One of the directions of the Centre’s work is to popularise archiving. Why are archives actually interesting and how do they help to understand the city?

The archive is a meeting place for different generations, and people from different time spaces. Just like history in general, it is important in shaping human traits, such as empathy and imagination. After all, without imagination, it will not be possible to understand people who lived in other times. And without imagination, it will not be possible to conceive the radical, striking novelty of a certain historical era.

The archive has a giving component. By creating and preserving works, we share them with people from the future. We imagine these people and leave them a message.

How many archives have we lost?

The Ministry of Culture forbade the publication of any news regarding the displacement of collections during the war. I only know that the SBU archive was destroyed in Chernihiv. Due to this, we lost extremely valuable materials forever, in particular personal files of prisoners and repressed people from the Second World War.

However, this is the fate of any archive. Archives are never complete. They are just selections that show some particles that have survived to this day.

Many new collections are also being created now. People began to actively document, archive, and collect materials. Perhaps, this is how we resist the war: in the face of total destruction, we are trying to preserve certain things. It helps to cope with terror and find shelter.

Another focus of the Centre’s research is the life and reconstruction of Ukrainian cities after two world wars. What research results could we apply now? How would you recommend working on urban regeneration?

The modern approach to reconstruction is to build the city of the future. A city cannot be a repetition, even if we speak about the most remarkable landmarks that existed before.

However, it is important to enter into a dialogue with history. It is necessary to understand where and how to show not only the beauty and positive aspects of the past, but also the wounds inflicted on the city. Destruction is part of history, and it must be in the new future.

We will not be able to rebuild the city as it was. And we will not be able to create a completely new city. However, the dialogue between the past and the present will always develop in the context of life after the war.

You often talk about monuments in your articles and interviews. Today, the issue of decommunisation is relevant again. How do you feel about the dismantling of monuments to Russian figures?

Of course, at least part of these objects should be removed from the public space. However, it is a pity that there is no greater initiative for their museumisation. Current preservation projects belong to separate institutions or collectors and are often more like cabinets of curiosities.

Many monuments were destroyed during dismantling. Thus, we have lost the basis for critical thinking and discussion. The same applies to the discourse on the decolonisation of textbooks and school courses. If we do not study Pushkin at all, we will not be able to talk about our own colonial complexes and work through this experience.

Our school courses and urban spaces should not just be collections of dead white men on pedestals, which we celebrate as something beautiful. We must be critical of our heritage and not forget its dark side.

Brutalist compositions also came under attack in the western part of Ukraine. How to determine which heritage is valuable?

Only a handful of very wealthy countries can afford to maintain a large number of their monuments in an unchanged form. This is the entry into the post-industrial world, in which consumer society, tourism, culture, and entertainment – everything that defines the Western world – are important. It was there that it became possible to preserve and restore not only the oldest, most valuable, and most beautiful monuments but all the best things in the world up to our time.

In Germany, the status of cultural heritage and the corresponding benefits are even given to buildings that were built just recently. For example, projects of prominent architects. The Germans did a great job: they studied the cultural heritage of all centuries and decided on what is considered the most important in the architecture of each period. This is a big material investment.

We must calmly admit that Ukraine is still largely an industrial country. That it does not belong to that privileged minority of the world that can maintain all its monuments. The involvement of civil society in the discussion about the value of Brutalist objects can help us. However, it is obvious that until we take care of the heritage of past centuries, Brutalist compositions will remain marginalised in the minds of the majority.

In addition, the heritage preservation boom is a relatively recent phenomenon. Throughout all the previous centuries, no one bothered to preserve buildings in their original form. They were constantly rebuilt, destroyed, and moved – everything that would be practical for life was done.

The truth is that we will not be able to preserve and maintain everything in an unchanged form. It is necessary not only to restore abandoned buildings but also to find new uses for them.

How to approach the renaming of toponyms with concern for the city’s history?

Our director, Sofiia Diak, is a member of the Lviv Toponymy Commission. As far as I know, she uses this opportunity to mark the names of women of different nations on a map of the city. If we are already removing something, we can at least try to add a positive program – not only national-patriotic but also an inclusive one.

It seems to me that many of the Centre’s activities aim to interest people in studying their history. In your opinion, are Ukrainians interested in the history of their country and their cities?

The people of Lviv are definitely interested. Locals are excited about many historical topics. One of the most popular events in our public program over the years was a lecture on Austrian-era sewerage. Back then, there were so many people that they were sitting on the windowsills and looking into the hall through the windows.

This is a great example of how topics that apply to our everyday life resonate in history. Everything we do today — kill each other, eat, sleep, marry, have children, and do research — has its historical aspect in the past.

Whether we like it or not, we are constantly reaching back to our previous experiences. For example, in the war of Russia against Ukraine, much is determined by the understanding of the history of the socialist block: where and what planes or tanks are left, and how they can be transferred.

After the full-scale invasion of Russia, the interest of Ukrainians in their history and heritage increased significantly. What advice would you give to people who have never delved deeply into these topics to get started?

I think the slogan of the movement of the social history in Great Britain is appropriate here: dig where you stand. You should start with yourself, your family, and your circumstances.

Many people are fascinated by heroic war stories. Indeed, they are very emotional. However, I believe that it is necessary to recognise important things in everyday life and to understand that everything you do today is part of history.

I think that realising that people from the past did things in a completely different way is the kind of experience that gets people interested in studying history – for the sake of meeting with radical otherness. Do not look for thought leaders, but look deeper into your history.

Interview: Nadiia Railko

Stories

-

Katarina Mathernova: If Ukraine had a human face and a human spirit, it would be 10-year-old Roman Oleksiv

-

A regional mission to drive social entrepreneurship: the story of Ksenia Kosukha

-

EU restores safe water supply for 100,000 Ukrainians affected by war

-

Promoting IT during the war: Lviv IT cluster and how EU4Digital helps

-

Frontline digitalisation: Kharkiv IT Cluster collaborations

-

How EU4Youth is driving opportunity and success among young Ukrainians