The energy year 2023: Europe has won the battle against Russia, but the struggle is still on

The warm winter and the supply of liquefied natural gas (LNG) helped EU countries escape the trap of dependence that Russia has been preparing for decades and that has worked with countries such as Armenia and Belarus.

Even though Russian gas imports more than halved this year (from 140 bcm to 60 bcm in 2022 (with total consumption of about 400 bcm), the EU was able not only to accumulate enough gas in storage but also to organize its consumers to cut consumption as much as possible.

Germany has declared that it has stopped buying Russian coal, oil and gas. Italy’s Edison announced that it had stopped buying gas from Russia as from 31 December. The United Kingdom also refused to buy Russian LNG.

Finally, Gazprom admitted that gas exports almost halved last year, from 185.1 bcm in 2021 to 100.9 bcm in 2022.

The decision taken by the EU in the spring to reduce Russian gas consumption has been consistently implemented, which is a vivid example of how the European Union can act together and achieve complex goals despite the diversity of its membership.

However, it is too early to talk about the final energy victory.

2023 may remain a challenging year for European consumers.

High gas prices may persist for a long time, despite the market drop in gas prices from December 2022 to January 2023.

The explanation is simple: while further implementing a strategy of shifting away from Russian gas, EU countries will still have difficulty finding alternatives on international markets. This will require additional funds to find global partners and difficult decisions within the EU.

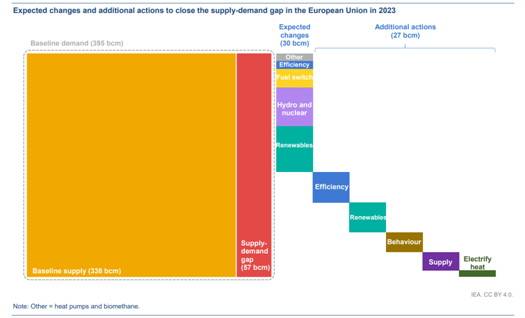

According to the International Energy Agency, if the EU completely abandons gas from Russia in 2023, subject to certain conditions, the need for 57 bcm will remain “uncovered,” of which 30 bcm can clearly be found, and 27 bcm will require additional efforts from all EU consumers – further improvement of energy efficiency, use of renewable energy sources, and electrification of heat.

What does this mean for Ukraine?

This means that some EU member states will continue to hear populist politicians calling for the need to maintain strategic cooperation with Russia and seek compromises to obtain cheaper energy.

Some countries and companies will likely continue trying to find workarounds to import Russian gas. Advocating for the EU’s decision to ultimately abandon Russian gas (including LNG) is unlikely to be easy.

2023 may be the year that determines whether Russia will maintain a minimal presence in the EU energy sector through lobbying and blackmailing or whether it will finally leave the European energy market with minimal chances of returning.

However, even if Russia maintains a minimal share of gas supplies to the EU after 2023, it will still be unable to return to the old “divide-and-conquer” algorithm.

The EU countries have realized the goal set by former European Council President Donald Tusk to start joint gas purchases within the Energy Union. The European Commission established the EU Energy Platform, which brought together European businesses, including market participants, to coordinate gas purchases through joint negotiations.

In December 2022, EU energy ministers also agreed on a draft EU Regulation on joint gas purchases. In addition, a decision was made on the so-called price caps (price ceilings) for gas – they will be applied if the gas price in Europe is higher than €180 per MWh for three consecutive days.

For comparison, in January 2023, wholesale gas prices on the Dutch TTF were around €70 per MWh.

In contrast to energy suppliers’ alliances, a powerful alliance of energy buyers is being formed, which will certainly make buying and selling gas more complicated and profitable for gas importers.

Russia is unlikely to stand idly by as the EU’s negotiating position strengthens.

The Kremlin will continue to look for opportunities to unite gas suppliers and transporters in the EU around Russia.

The top Russian and Turkish leadership is already writing a roadmap to make a gas hub in Turkey – it would “depersonalize” the origin of gas and sell Russian (and possibly Iranian) gas to the EU with other parameters of origin.

However, it is too early to consider these negotiations a serious problem. According to the Turkish side, preparations for the gas hub will take a year, so their content may still change significantly, given the elections in Turkey and Ukraine’s expected victory in 2023.

In addition, Turkey does not see itself as a partner that would work faithfully for Russia’s interests. With the increase in its domestic production and the opening of LNG terminals, which can be accessed by countries dependent on Russian gas, Turkey is becoming a competitor to Russia rather than a like-minded partner.

In addition to Turkey, other gas-supplying countries may become Russia’s situational allies in the gas sector, particularly in blocking the decision on price caps for the EU.

Algeria, one of the largest gas exporters to European consumers, has already expressed its disagreement with the EU’s initiative.

Of course, Russia will try to take advantage of the corruption scandal around the European Parliament and Qatar in response to the allegations of bribery against certain European Parliament officials, the Qatari mission to the EU made a statement that this would have a “negative impact on regional and global security cooperation, as well as discussions on global energy.” Of course, the Russians will do everything to deepen this conflict between the two sides.

The year 2023 will be transitional in the global gas market as it will form new alliances and rules of interaction between gas buyers and sellers.

Russia is likely to increasingly agree to the conditions set by its partners (Turkey, China, or Asian countries) rather than dictate its policy.

Instead, gas suppliers from Africa and the United States will enter the global market more boldly.

The US-European gas trade will be another step towards greater unification of Western countries and countering energy blackmail, which has already been used by Russia and may be used by other authoritarian countries rich in natural resources.

European Pravda

PHOTO: AFP/EAST NEWS

Media, Publications

-

Respect and recognition

-

Eurobarometer shows strong support for Ukraine

-

New EU Strategy for the Black Sea Region

-

EU and UNDP in Ukraine transfer equipment to Lubny Medical College and Lubny City Primary Health Care Center

-

Happy birthday, invincible capital!

-

Justice matters most when people can feel it working