Producers of traditional Ukrainian cheese go for growth with EU support

14/11/2022

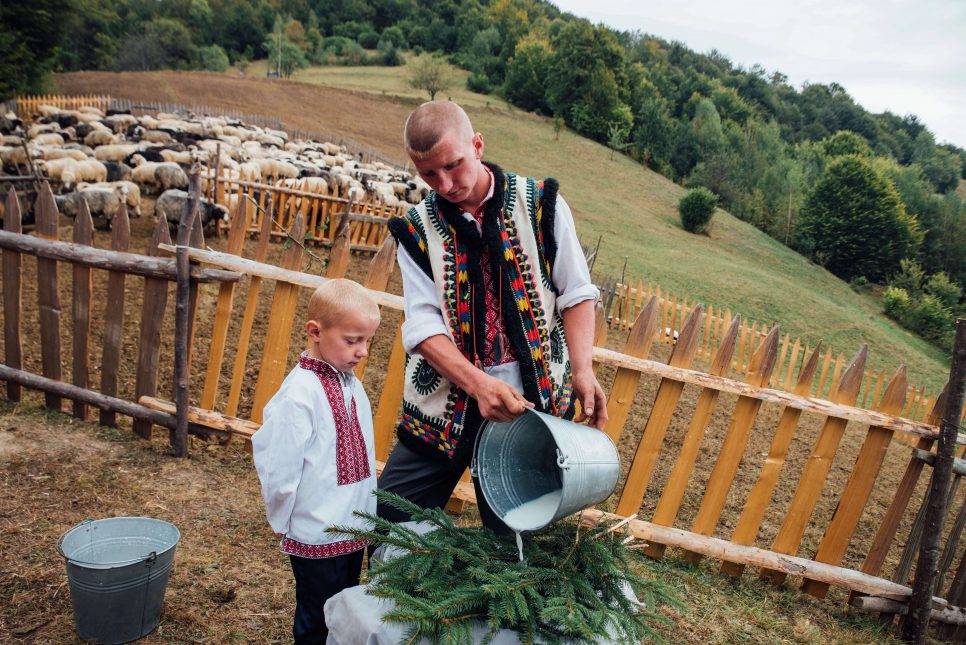

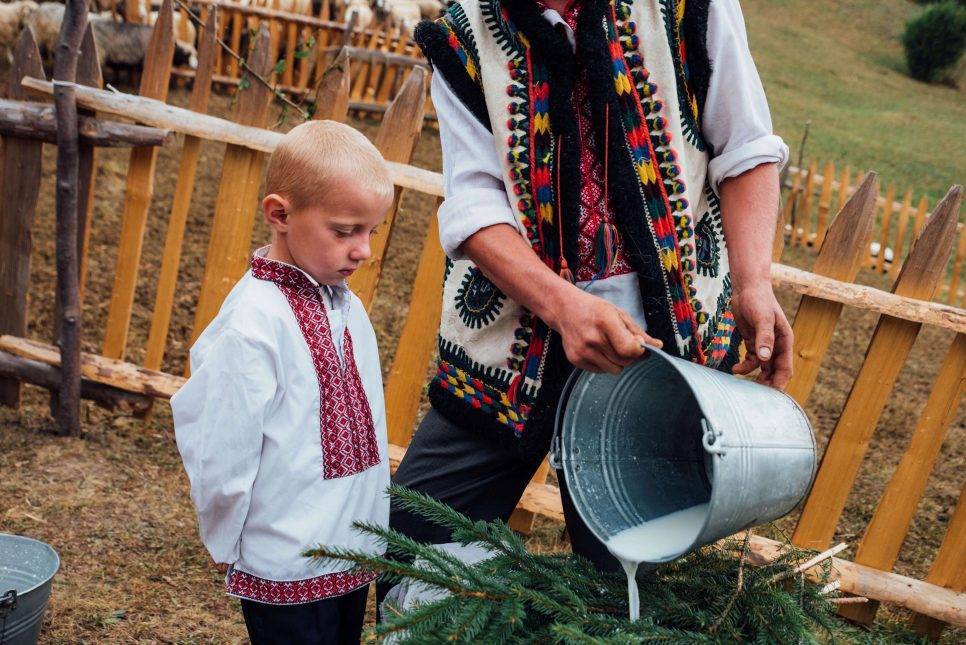

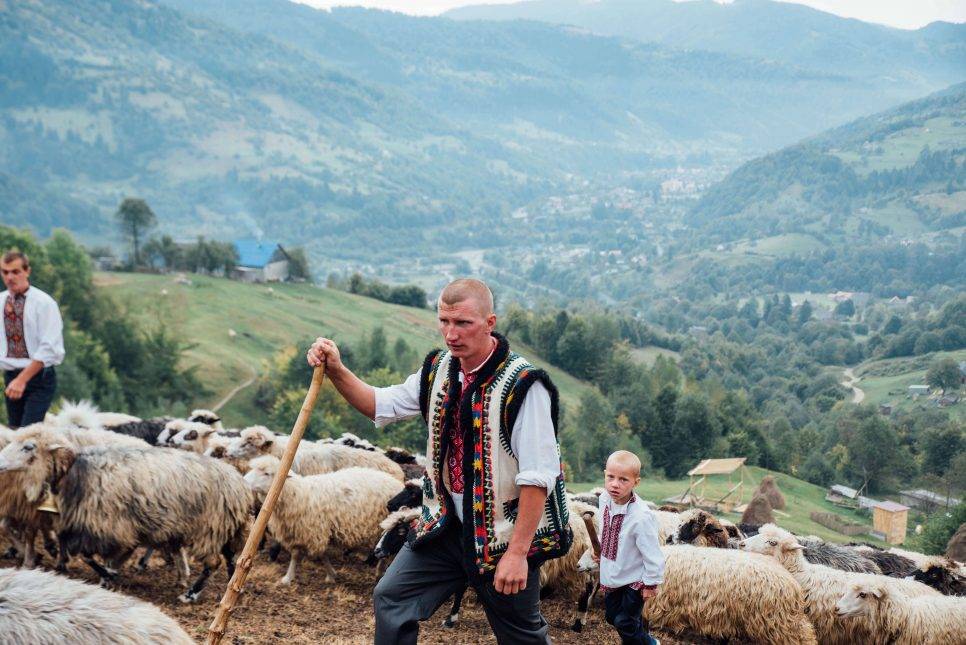

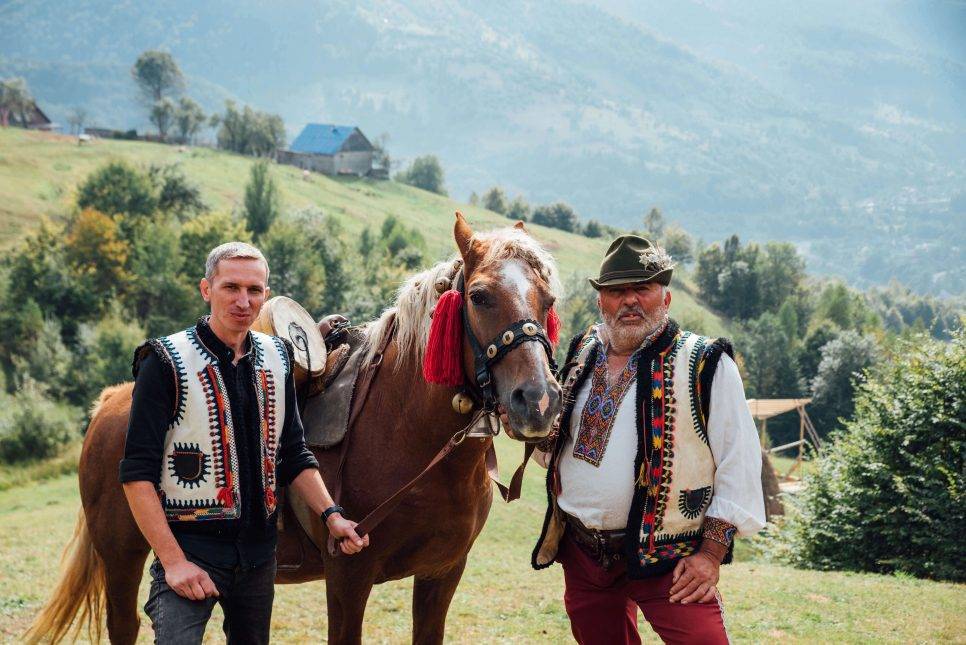

In the Carpathians, Ukraine’s highest mountain range, live the Ukrainian highlanders – the Hutsuls. Apart from their distinctive language, music, traditions, and costumes, there is one more thing that Hutsuls have maintained for centuries – their traditional way of making the first-recorded Ukrainian cheese, Hutsul bryndza cheese, made from sheep’s milk.

Sheep breeding has played an important role in the economic survival of Hutsul families, giving them not only wool and milk but other dairy products. The first written evidence of Hutsul bryndza cheese goes back to the 15th century, showing the cheese was made with the same recipe and using similar technology over 500 years ago.

Some believe Ukraine’s cheese-making traditions stretch way further back in time than that, however.

“I believe that Hutsuls used to make it way earlier, maybe even a thousand years ago,” says Oleksandr Martyn, the Head of the Association of Producers of Traditional Carpathian Highland Cheeses. Until the 20th century, literacy among the Hutsuls remained very low, so Martyn thinks non-written evidence might date back to as far as the 11th century.

What makes it unique

Martyn, himself a cheesemaker, talks very passionately about the distinctive characteristics of Hutsul bryndza cheese, noting that the sheep that produce the milk for it have to graze at least 700 meters above sea level. The reason for this is that at such a high altitude, there is a unique variety of plants for them to graze on, and the properties of that unique blend make it first into the milk, and then into the bryndza, he says.

“In the Ukrainian Carpathians, there are about 64 plants from the Red Data Book,” Martyn says, referring to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of rare and endangered species.

“People there usually wake up at 5.00 a.m. Some make breakfast, some clean tools, others go about other business. At about 5.30 a.m. the sheep are taken to graze until dinnertime. They cover about 30 kilometres a day, eating berries and plants that are in the Red Book. So our sheep eat the best food in the whole of Ukraine. The final product is the milk, and then the cheese.”

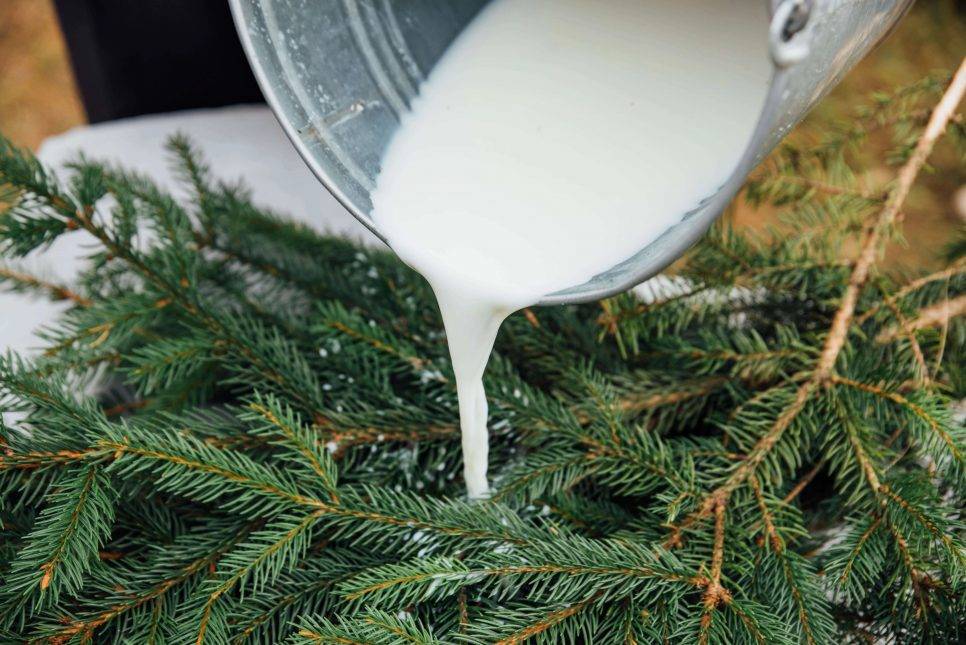

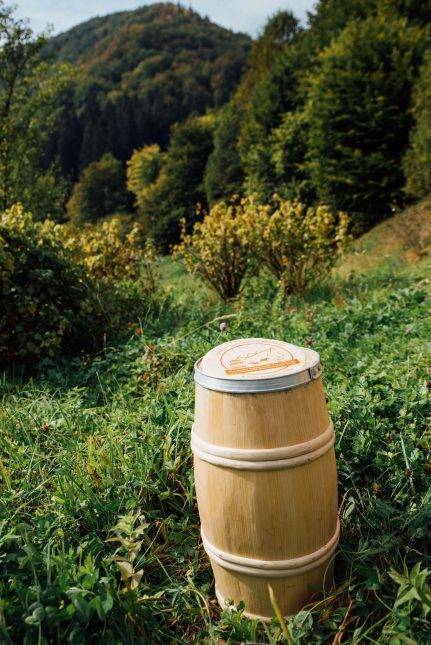

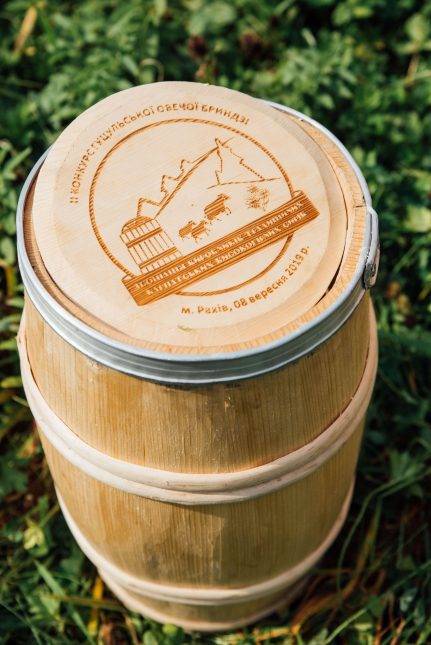

The cheese is made using an old, traditional recipe that does not include any chemical additives and that has been passed down from one generation to the next for centuries. The cheese is matured in a cellar-like environment, at a temperature of 4 to 6 Celsius, in wooden barrels. During the maturation process, various bacteria from the milk interact with each other, improving both the health benefits and the taste of the cheese. According to Martyn, the number of these bacteria reaches over one million. As a result, someone who eats the cheese gains exposure to many of these different bacteria – both good and bad.

“It turns out that if sometime in the future this person has a serious disease, the body may have already been exposed to some of the bacteria through eating the cheese,” Martyn says. “Therefore the person has a strong immune system and a better chance of recovery.”

“I fell off a motorcycle last year and ate a lot of cheese to help me with my recovery. I was back on the motorcycle in a couple of weeks.”

Power of knowledge

To help develop traditional cheese production in Ukraine, the Association of Producers of Traditional Carpathian Highland Cheeses was founded in 2018 with the help of the EU-supported Institutional and Policy Reform for Smallholder Agriculture project under the EU4Business Initiative. The project contributes to more inclusive, competitive growth-orientated agriculture that respects the environment, increases rural incomes, and slows down rural-urban migration.

Taras Antonyuk, currently a national expert in rural development with the project, brought together people involved in making Hutsul sheep-milk and cow-milk bryndza, as well as tour guides for high-mountainous areas. Some of them became members of the association.

One of the guides was Martyn.

After the very first meeting of the association, Martyn was so inspired that he not only joined the team but later bought some sheep and became a cheese producer himself. He takes care of marketing, while his friend Dyma oversees production.

Martyn, who lived in Rakhiv, a town in Zakarpattia Oblast in western Ukraine and home to many ethnic Hutsuls, did not know anything about Hutsul sheep bryndza before. “I learned everything through the project. Imagine it: I lived in this city and wasn’t eating this cheese!” he says.

Over the next few years, the association held several gatherings at which the project team brought in experts to share knowledge with members. Martyn remembers how experts from France told how a local cheese association had increased production and attracted more tourists to the region for gastro tours.

“They showed us how real-life models would work,” he says.

Soon enough, Martyn was able to use this new-found knowledge to produce real-life success.

“When I came to the association, and we produced our first cheese, the price was UAH 150 (EUR 4). This was even lower than the cost of production,” he says.

“Then we started learning, we underwent external quality control with the project’s support, and we started selling cheese for UAH 600 (EUR17) instead of UAH 150.”

The project also financed a tour to Austria’s Tyrol region, where Martyn and other association members, including other cheese producers, learned from the locals’ experiences.

“We all came back in great spirits, with new ideas, and the desire to improve the situation in our country and to develop further,” he says.

Now he and others are trying to revive the centuries-long tradition of making the cheese in wooden barrels, as the same maturation processes do not occur when the cheese is matured in glass containers.

Another idea born from knowledge-sharing was food tours – a new phenomenon for Ukraine. Martyn says that while regular tourists spend EUR 50 a day on food and other things, gastronomical tourists spend over EUR 200. “They get to know the area through the local cuisine. So people can make four times more.”

The association created such a tour in 2021 to both preserve and popularize the traditional culture of high-altitude sheep and cattle farming in the Ukrainian Carpathians – an element of the cultural heritage of Ukraine. The plan was to develop a cultural-tourist route with at least 13 locations. They got financing through Ukrainian Cultural Fund, brought bloggers to the location, and shot a promotional video that became very popular on the Internet.

“If it hadn’t been for the war, tourists would now be traveling along our gastro-tour route,” Martyn says, referring to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. “There’s no tourism as such happening just now.”

But that’s not the only impact the war has had on the production of Hutsul sheep bryndza in Ukraine. The number of people who knew about the old traditions and technologies for making this cheese was already low. The war has further decreased the number, as some went off to fight, while others had to flee the country.

Despite these challenges, Martyn still looks to the future with hope. He wants to create a kind of service sector cooperative to ease the work of cheese producers, who at the moment do everything by themselves, from production to marketing, to retailing, and don’t have enough time to concentrate on any of them.

“I want people who know how to make cheese, to make cheese,” says Martyn. “Those who know how to sell it, (should be able to concentrate on) selling it. People with knowledge of design should be involved in that area.”

“And I really want to see tourists coming to Rakhiv and learning about the area through gastronomy,” he says. “It would increase sales, and locals would get more benefits overall.”

Stories

-

Katarina Mathernova: If Ukraine had a human face and a human spirit, it would be 10-year-old Roman Oleksiv

-

A regional mission to drive social entrepreneurship: the story of Ksenia Kosukha

-

EU restores safe water supply for 100,000 Ukrainians affected by war

-

Promoting IT during the war: Lviv IT cluster and how EU4Digital helps

-

Frontline digitalisation: Kharkiv IT Cluster collaborations

-

How EU4Youth is driving opportunity and success among young Ukrainians